I spoke to my friend the philosopher Evan Selinger about this. He’s written for years about the social, civic and existential effects of technology.

In recent years Evan (working with his colleague Woodrow Hartzog) has been advocating for a complete ban on facial-recognition technology — he thinks it’s a true slippery slope. (Here’s a New York Times op-ed by them, and a longer paper making the case.) But because Evan’s a philosopher who likes to be precise about things, he’s also tried to pin down some rules or metrics we can use to discern a real slippery slope from a mere moral panic.

I wanted to know his rules!

So I called him up to talk about it, and here’s an edited version of our conversation:

Why slippery-slope arguments are often wrong

Clive: Philosophers generally regard technological slippery-slope arguments as bogus. Why?

Evan: In debate club or logic class, you get this idea that slippery-slope arguments are almost always fallacious. They’re overly speculative and imagine worst-case scenarios without presenting a credible account of how we get from A to B to C.

Clive: Right — they’ll assume that technology has a mind of its own, and that humans are helplessly steamrollered by its power. That once you let a new tech genie out of the bottle, it has a force totally huger than human agency.

Evan: And, of course, those accounts have been widely debunked. Technological forecasting is a notoriously complicated process. So if you’re going to make a slippery-slope claim about technology, you need to have a credible story about why your causal expectations really do seem to line up. Not mathematically precise, but plausible.

The first sign of a real slippery slope: “Strong affordances”, new powers the technology gives us

Clive: But you think sometimes there really are technological slippery slopes — tech that pushes us in a bad direction really strongly. How can you tell when we’re facing a real slippery slope technology? What makes that technology have such power?

Evan: You need to talk about affordances and incentives. What affordances does the technology have? And what incentives does it offer people?

Clive: What do you mean by “affordance?”

Evan: What I mean is the transaction costs of doing an activity. What transaction costs does the new technology diminish? What transaction cost does it impose? A gun, for example, radically diminishes the transaction costs for ending life almost effortlessly at a distance. A gun can’t force you to kill anybody. But it’s going to be predominantly used in ways that capitalize on its affordances.

Clive: Its affordances are focused towards sending a piece of metal really, really, really, really fast in one direction.

Evan: Or we can think about the technologies of writing. If we talk about the shift from the typewriter to the keyboard and writing online, one of the dominant reasons there’s so much trolling and toxic material circulating is because the transaction costs of being able to communicate have gone down precipitously. With the Internet, unlike in the past, I don’t have to write my strongly-worded letter that I slowly proofread and make sure my penmanship isn’t embarrassing, or write out the person’s address on the envelope, get a stamp, and bring it to the post office. There’s enough speed bumps that it slows you down. If you’re going to write that letter, you must really be angry and pissed off.

“Typewriter”, by Michaela Pereckas

Clive: Whereas with the Internet, the transaction costs are so low that we’ll post all the time about even minor annoyances. That’s an affordance of the Internet: Really low transaction costs on communication.

So to identify a slippery slope, we start by looking for …

Evan: … strong affordances.

Clive: Right. So the new technology really changes transaction costs a lot. It takes something that used to be really hard, and makes it really easy.

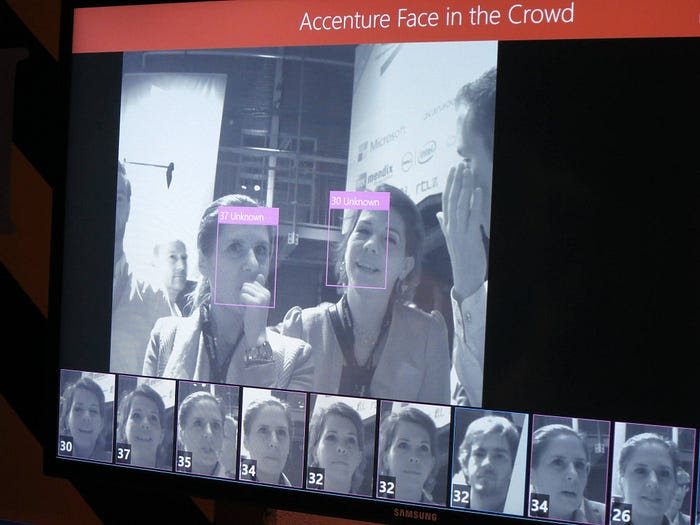

Evan: Facial recognition technology has a very distinctive affordance — which is, if it works well, it identities who a stranger is. That’s a major game-changer in terms of power dynamics. Historically free association has largely been safeguarded because the transaction costs of identifying strangers were protected by a natural default state of obscurity — meaning, there’s only so many names and faces we can recall. There’s a biological limit to that. And we didn’t have technologies that could radically reduce transaction costs of determining who someone is. We’ve experienced nothing like face recognition before, which is why there are major gaps in the law.

Bottom line, what is face recognition good for? Since it’s good for identifying strangers, that will be how it’s used. And since it also lowers the cost of doing related things like affect recognition — using software to infer what mood or emotion a person’s face conveys — it will be used for that purpose, too. The costs of building upon the foundation of automated face recognition are very, very small.

The second mark of a slippery slope: When people have clear incentives to abuse a new technology

Clive: So to identify a slippery slope, you look for strong affordances. Face recognition has them. But you also mentioned “incentives” — what incentives a new technology offers. You mean … how does it line up with the pre-existing needs and desires of people, corporations, governments? What incentives do we have to use or abuse the new tech?

Evan: With face recognition and related technologies, it’s a perfect storm. You have law enforcement wanting to identify who strangers are for security purposes and possibly make inferences that predict who could erupt in violence. Retailers have security concerns too, and many would love to know who is looking at what products.

And there’s also all kinds of seemingly banal things — like making things more convenient by using your face as an ID, so you don’t have to wait in a long line to board an airplane or enter a concert. Or, in education, instructors are being told they need more information on whether students are engaged or bored.

Clive: Or whether they’re supposedly cheating, as with proctoring software.

“Face recognition”, by Mirko Tobias Schäfer

Evan: If a picture tells a thousand words, our faces are very expressive. We’ve never had anything in the history of civilization like the prospect — and promise — of being able to computationally analyze faces in incredibly cheap ways and provide so much perceived utility for so many different vendors.

A couple of years ago, Andrew Cuomo — the former governor of New York — talked about the tolls coming in and out of New York. And he basically said, well, if we can scan license plates to see if people have outstanding warrants … why would we only do that? That would be such an underuse of this utility! Given the low cost for doing all these things, why aren’t we getting bang for the buck?

It’s the same thing with face recognition technology and surveillance creep.

Clive: Once a government has it, they have the incentive to use it everywhere.

Lastly: Are there roadblocks to stop a new tool from being used in terrible ways?

Evan: When considering slippery slopes, it’s crucial to ask: What are the roadblocks? What would stop us from excessively developing this technology?

Unfortunately, that’s the problem with face recognition technology. There are some protective measures, even bans. But overall, in the U.S., there are far too few roadblocks. It’s hard to challenge the longstanding assumption that, for the most part, people don’t have a reasonable expectation of privacy when they’re in public.

Clive: Very true. Even fifteen years ago, there would have been high computational costs. And cameras cost more back then, and were more rare. But that’s all receded to nothing: I mean, cameras are everywhere, and computation is very, very inexpensive in the cloud. So some of the practical roadblocks are basically gone.

Evan: You can see huge vacuums here that include significant policy gaps.

I would add one more point: One of the things that makes the affordances of facial recognition technology so unique and pernicious is that we bring our faces with us everywhere.

Our phones track us, but we don’t have to bring our phones everywhere. We don’t have to bring our computers. But wherever we go, we bring our face. And our face is the perfect conduit between our online lives and our offline lives.

In contrast, what does a *false* slippery-slope argument look like?

Clive: Okay, so you see face recognition as a true slippery slope. It hits all three of your principles: Really strong affordances; plenty of motivations for state and corporate actors to roll it out; and few roadblocks. If we don’t stop it quickly, it’ll be everywhere.

But what does a false slippery-slope argument in technology look like? What’s an example of a technology that people thought was going to deform life, but didn’t have the same interlocking combo of powerful affordances, motivations, and no roadblocks?

Evan: I’m shooting from the hip here. But I think that when texting first came on the scene, there were concerns that this would be a slippery slope towards the erosion of formal language. Critics worried that people would become so habituated to casual texting that when we found environments where formal writing is required, we’d be less able to do it. We’d spend so much time texting that it would create a kind of intellectual atrophy, or it would rewire us.

And I think what we’ve seen is sort of the opposite. People have learned how to adapt and code switch. They’ve learned how to become, let’s say, especially contextually savvy communicators.

“Texting”, by Kamyar Adl

Clive: You’re right. The fear was that once people went through that door — and started enjoying writing in short forms and slang and casual language and emojis — they’d be unable to go back, and do formal speaking.

The affordances were there! Texting and chat really did encourage people to write in more casual, breezy ways, with lots of emoji. But the motivations weren’t there. People, particularly at work or at school, are motivated to write in more-formal ways. So they never got trapped in text-speak, unable to communicate in any other fashion.

Evan: Though I do think there’s a legitimate slippery slope potential here — which is some of the A.I.-driven automated forms of writing we’re seeing now.

Clive: You mean, all these forms of autocomplete that we’re seeing? Like where Gmail will now offer to complete sentences, and tools like GPT-3 are offering to write entire emails, documents, and presentations for us?

Evan: Yep. So, look at the affordances and motivation to be better than what they would come up with themselves because the advice comes from a machine?

I’m not saying this is a slippery slope that can’t be stopped. But I think there is a slippery slope worry here. The easier it becomes for machine intelligence to know our own ways of speaking — and to come up with things really quick — then given our own inertia and time-crunch, I think there’s a temptation for us to start to start feeling these AIs are just good enough. And that it’s not worth the effort to overturn them.

Clive: Right. When we’re doing formal writing at work — in emails or documents — it’s hard. It doesn’t come easily. So we’d be more motivated to hand the hard work over to the machine.

We didn’t have a similarly dangerous motivation with texting.